Review by Dan Harris

Unmade in China was written from the perspective of an entrepreneur who for nearly 20 years has sourced products from and sold things to China. This micro perspective both enlightens and limits the book.

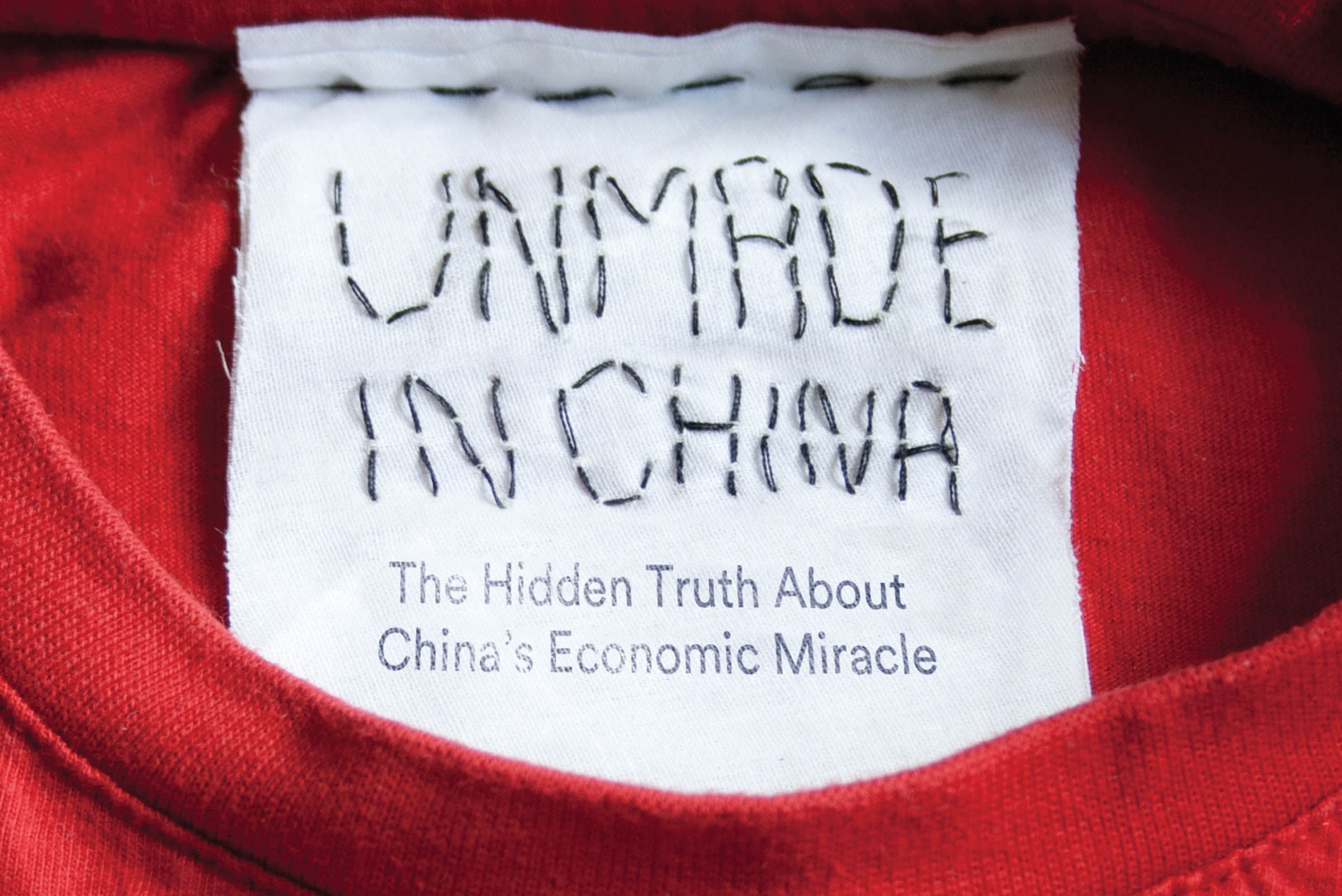

The book’s primary contention is that when it comes to China, metrics like GDP and trade balances are inaccurate and take our attention away from China's real threats and opportunities. Haft wants us to see China from the perspective of someone (like him) with an extensive history of working within the engine room of China’s economy because it is from this perspective that we will best understand China.

The book sets out to debunk the following three “myths”:

- China’s Economy is about to surpass the US

- Everything is made in China

- China’s currency manipulation kills jobs

Haft contends that we give too much credit for the good that comes from China while failing to realize how much bad comes from China, especially when it comes to product manufacturing. Haft plays up how so much of what China manufactures is really just assembled there from components made and designed elsewhere. He also highlights how so many of the products China makes are of abysmal quality.

Using recent case studies and hard data, Unmade in China vividly shows how China’s product chain is systemically risky. Haft uses the breadth of China’s outputs – food, drugs, toys, auto parts, electronics, oil rigs, refineries, bridges, nuclear reactors – to illustrate how goods move through concentric rings of danger as they are transformed from inputs to outputs with each step in the value chain only magnifying the risk that the final outputs will be unsafe.

Take baby formula in China. Please. Why would we think China is capable of developing and building high-end nuclear power plants or airplanes when it cannot even make safe baby formula? Haft sees China’s inability to make good products as an opportunity for US-made products and services to thrive in China and worldwide. Just consider what happened after melamine in Chinese baby formula poisoned over 300,000 infants in 2008: US dairy exports to China quadrupled. Bombarded by almost daily assaults of safety scandals, Chinese prefer American-made products over Chinese-made products and they are willing to pay a premium for products made in America.

I agree and I disagree. All that Haft says about China products is true on a micro level, but at the same time, more and more products both designed and made in China are competing worldwide. Are these top of the line products? Almost never. But they are oftentimes “quite good” products produced and sold at considerably lower prices than their competitors. Chinese brand cell phones are a perfect example of this. What about all the made in China products we buy every day that work just fine?

Unmade in China nicely debunks the notion that China’s economy is a juggernaut surpassing that of any other country. Haft takes apart this notion using cold hard facts. Of course, all one need do is Google “China’s economy” with a last six-month time restriction to see that this notion is in decline these days anyway.

But the book does a superb job reminding us that the US is still – in virtually all the ways that matter – a much richer country than China. Haft notes that the US has $40 trillion more in household, corporate and government assets than China. Anyone who has been anywhere in China outside its wealthiest neighborhoods already understands that China does not yet compare with the US on wealth, but some of the statistics Haft uses to prove this point are eye opening.

This book also does a good job (though it's certainly not the first to do this) of highlighting how so much of the revenues and profits from products made in China actually goes to the US. He writes of how nearly all of the revenues/profits from a $70 pair of US-branded sneakers made in China goes to the American companies that designed them and handled their transportation, warehousing, advertising and retail costs. The book, however, fails to account for how Chinese companies are increasingly taking on some of these ancillary services. For example, warehousing of products is increasingly being done in China, as is the transporting of products on Chinese made and owned vessels with Chinese crews.

Though Haft does a good job on a micro level explaining how the US benefits from using China for so much of its product manufacturing, like so many “China people” (this blogger included), he too often glides over the bigger picture. Those of us who work with China tend to formulate China’s big picture by adding up the “little” things we experience every day, whereas economists, historians and even journalists are able to have enough distance to better survey the big picture.

Haft’s arguments regarding our having overestimated China's prowess reminds me of a Forbes article, entitled, “One Way To Save US Manufacturing Jobs.” That article highlights a small Midwest windmill company that saved American jobs by moving a large portion of its production to China. The genesis for the Forbes article was a China Law Blog post, “China. Friend Or Foe? Opportunity Or Challenge? Or, Why Can’t We All Just Get Along?", detailing how one of my consultant clients had saved the jobs. All good, but if there were no China, this US windmill company would never have sent any jobs to China in the first place.

Examining China on a micro level is important and Unmade in China does a very good job with that. But like so many non-fiction books I have read, it weakens by trying too hard to extend its micro analysis onto a grander, more macro stage. Does sending manufacturing to China really have no negative impact on an America where high school graduates 30 years ago worked at factories making $20 an hour, plus good benefits, but now pack boxes at warehouses for $11 an hour with minimal benefits? Does sending manufacturing to China strengthen our country? Does anyone really believe China is not slowly but surely closing the gap on product quality? What will happen then? Unmade in China does not seriously discuss these big issues.

Dan Harris is Managing Partner of Harris and Moure, PLLC (an AmCham China member company) and an active blogger at the China Law Blog.